Scientist Spotlight

Who are you?

Many of my friends and colleagues refer to me as Sun for short! I am currently a research assistant at the Tropical Marine Science Institute, based at the St John's Island National Marine Laboratory.

I lived in Beijing, China, for six years for my secondary education before obtaining a degree in Marine Biology at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Hence, from my upbringing, I like connecting and exploring new places with new people, which allows me to be open to new life perspectives!

What are you researching?

I assist Teresa and Dr. Neo Mei Lin, Giant Clam Girl, in the mariculture scene. We nurture and care for St John's Island's giant clams and cowrie snails. We focused on developing and enhancing culturing methods in local seawater conditions to improve our comprehension of marine animal conservation.

Additionally, I revisited a niche study on experimenting with the acid secretion of the juvenile giant clam (Tridacna crocea) to understand its burrowing mechanism within the coral reef ecosystem. Acid secretion provides chemical bioerosion within the coral reef, eroding calcareous rocks and releasing soluble calcium. This changes the chemical composition of calcium, carbon dioxide, and bicarbonates in the water column, affecting the calcification and photosynthetic rates of animals (e.g., corals and giant clams) within the reefs.

I will also be hopping over to a new seagrass project, where I will assist Dr. Ow Yan Xiang in assessing the effect of nutrient thresholds on seagrasses in an eutrophic environment. As Singapore goes through urban development, it is critical to understand the impacts of discharged nutrients on proximity coastal habitats such as seagrass meadows to manage nutrient cycling better, maintain water quality, and sustain ecosystem resilience.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Southeast Asia has high marine biodiversity, so it is a significant hub for the aquarium trade, in which giant clams and cowrie snails are common trading animals. There is limited information on culturing giant clams and cowrie snails in Singapore, so large production of these animals is deemed challenging. Therefore, with a more detailed understanding of the physiology and the culturing methods of giant clams and cowrie snails, the project hopes to increase awareness of the plausible sustainable culturing for aquarium trade while assisting future interdisciplinary research and conservation work.

Seagrasses seem somewhat neglected while playing an essential part in the ecosystem as a habitat. They provide many beneficial services to the ecosystem and human societies, such as maintaining biodiversity, shoreline protection, and accumulating blue carbon. As climate change becomes more evident, awareness and understanding of seagrass, a nature-based solution, are also necessary.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I joined TMSI in May 2023, so I am still relatively fresh! As my interests lie in marine water, TMSI has been a place that I wanted to explore, where outstanding marine research has been conducted and published! After joining the institution, I felt that the people and company stood out the most here, where I felt I was looked after and cared for.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

Rock pools!

As an animal lover, I find rock pools super cool because that’s where fascinating marine animals can be found. But I chose rock pools because of the scene, where lots of stuff is going on simultaneously, such as the rocks being eroded in time, predators and prey playing hide-and-seek, tides coming in and out with scorching Sun beaming, etc.

During my undergrad in Melbourne, I drove to Cape Schanck with my friends to observe Aurora until sunrise at the rock pools. It was all chaos with huge waves and strong winds, but looking into the sky and horizon made me calm and collected. It speaks to me how peace can be understood.

What are your hobbies outside of research?

Like most marine biologists, diving is a must. Just as curiosity takes me, I will always drag the diving group as I’m always behind finding animals. I also take photographs, either on terrestrial ground or underwater. I love capturing different angles and moments of nature. Outside of nature, I spend most of my time playing basketball to keep my body and brain active. In doing so, I also keep myself fit through regular exercises to prevent myself from injuries as much as possible.

Who are you?

I come from a diverse career background. I attained a diploma in Biotechnology and started off as a police officer for about 8 years. I then became a retail assistant for 5 years and had short stints in a clinical lab and in an estate sales office. I am now a lab technologist at TMSI. At TMSI, it was mostly on-the-job training for me.

What are you researching?

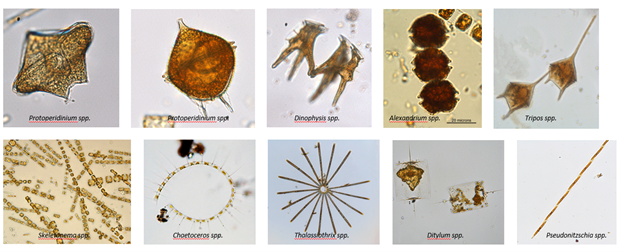

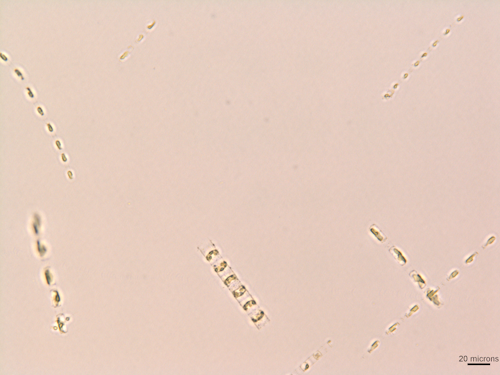

My main area of research is marine phytoplankton para-taxanomy and quantification of phytoplankton with a focus on diatoms and dinoflagellates, via light microscopy. I may also at times assist in phytoplankton quantification techniques using flow cytometry.

Identifying down to species-level is often impossible only with the use of a light microscope. With such a constraint, the para-taxonomy method is used for the identification of marine diatoms and dinoflagellates. Under the maximum objective magnification of 400x, I would perform identification only based on recognizable external morphological characteristics of the marine diatoms and dinoflagellates. This usually means identifying them down to genus-level.

The data from identification and enumeration of diatoms and dinoflagellates is an integral part of the biological aspect in the environmental water quality monitoring regime.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

I believe the increased understanding of taxonomy and morphological diversity can also contribute to other emerging interests in traits-based analyses of phytoplankton communities and their responses to the environment. The data potentially gives insights into the environmental status of seawater and the conditions that support the initiation and maintenance of nuisance algal blooms.

Under specific optimal conditions, a certain species of phytoplankton may proliferate quickly and take the form of a phenomenon generally termed as a “bloom”. For example, there are the regular occurrences of Chaetoceros spp. blooms at the West Johor Straits. Most Chaetoceros species float in the seawater due to their setae (spines), which are long and overlapping for most species and these can damage fish gills and cause fish death events.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I joined TMSI in April 2013. Back then, TMSI was located at St John’s Island! The idea of working on an island, away from the bustling city and crowded lunch places, was very attractive. Also, the name of the institute’s building, “S2S”, stood out to me when I found out what it stands for – Sea to Sky! TMSI is indeed a multi-faceted institute where many researchers perform various work experiments from the sea to the sky.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

I would most like to live near freshwater instead of the ocean. I love the idea of living in a kampong next to a river stream and nearby a waterfall!

What are your hobbies outside of research?

I love volunteering my time to do community art, usually organized by the local Community Centres and Peoples’ Association, like the mural art at the Salvation Army and Façade Art at HDB blocks. I was also involved in the art installations for Chingay since 2020.

Who are you?

I am a Research Assistant at TMSI and have a degree in Biotechnology. I picked up flow cytometry (FCM) when I started working in TMSI.

FCM involves the usage of a machine called a flow cytometer that is equipped with a laser that analyses cells in a liquid medium. For each analysis, scatter and fluorescence signals are collected. Scatter signals provide an estimate of cell size and cellular characteristics, while fluorescence signals reflect the biological or biochemical statuses of the cells.

There are two main types of flow cytometers: analysers and sorters. An analyser allows the user to carry out solely sample analysis, whereas a sorter has the ability to analyse samples and allow for the selection of populations of interest to sort them out individually into fractions.

The benefits of using FCM includes its ability to provide a rapid and sensitive analysis mode especially for organisms not visible to the human eye. It is also a versatile technique that can be coupled with dyes or substrate to provide information on the biochemical or biological statuses of the organisms like phytoplankton that can provide an insight into environmental statuses, for instance, that of our oceanic waters.

What are you researching?

I have been working on the expansion of the usage of FCM in environmental research. Currently, as part of my routine work, I am using FCM to carry out analysis of marine phytoplankton that have a wide size range. Phytoplankton in the size range of 0.2-2 micrometres are of particular interest as they are almost impossible to be quantified via the human eye. Despite their small size, they are important contributors to primary production, via photosynthesis, and fuel food webs in the marine environment. They are also sensitive to environmental changes, making them good bioindicators.

Other than analysis of marine samples, I have used FCM in the analysis of freshwater, coral samples, and development of metabolic assays.

For freshwater samples, the aim of the study was to develop rapid enumeration methods for phytoplankton using FCM. Samples from reservoirs were collected and analysed to determine their concentrations and their fluorescence signatures. Subsequently, specific gating, a grouping strategy, for populations of interest were developed and verified by sorting out the captured cells for identification via microscopy. With the developed protocols, we were able to quantify the phytoplankton and provide identification based on the gatings.

For coral samples, we collected samples from a local species, Pocillopora spp., and used FCM to quantify the zooxanthellae and track the changes over time in their chlorophyll when we did concurrent in vitro heating studies. This allowed for a snapshot of the coral bleaching process, where zooxanthellae are expelled by corals when the waters get too warm.

Development of metabolic assays involve the addition of specific substrates that can be broken down by phytoplankton enzymes to provide an indication of the nutritional status of the environment. For this study, I utilised fluorescent substrates like ELF-97 and fluorescein diacetate, coupled with FCM, to allow for the prediction of either an environment that is deficient in phosphorus or nitrogenous nutrients. This can help us to better manage the waters we sampled the phytoplankton from.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Usage of FCM for environmental research provides an insight into the properties of smaller phytoplankton or viral particles. When combined with microscopy, it provides a more complete picture of the microbial environment.

Understanding phytoplankton is critical in the context of Singapore and the region given the issues we are facing. Coral bleaching is a real concern given that Singapore has already lost much of its coral cover. Figuring out their heat tolerance will be important for protecting what we have left and in restoration efforts. The prediction of environmental statuses could also be critical for better management of algal blooms and waste discharges.

Hence, I feel that when used in an appropriate manner, FCM can be incorporated into environmental research to increase the coverage of research topics and subjects to address environmental problems.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I joined TMSI in 2003. The chance to go out to sea and natural habitats for field trips, coupled with laboratory work, was the main appeal for me to join and stay at the institute.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

I would like to stay at the coast. From there, I can explore the intertidal habitats and enjoy the sunset and sunrise at the horizon.

What are your hobbies outside of research?

I like hiking and travelling.

Who are you?

I am a biologist. I have a Masters degree in marine biology and biological oceanography, and what I really like to do is coral reef ecology, but have worked on a bunch of other biological research projects. I like learning new things, so this is probably why I’ve ended up with a pretty wide variety of past research projects involving copepods and even bacteria.

What are you researching?

Currently I am lucky to be able to be able to work on my favourite ecosystem – coral reefs! We have just started a project investigating how we can make corals more resilient to rising sea surface temperatures. For a start, we are going to screen a lot of corals to see how they naturally are more or less tolerant to high temperatures. We will see if we can train the more heat-tolerant individuals to become even more resilient. We will also try out some interesting new methods, for example by adding helpful bacteria to see if it will help corals to become more resilient (just like how you take probiotics for your gut health).

TMSI scientists often have a bunch of different projects ongoing. For the last two years I was a member in a diverse team involved in setting up the Marine Environmental Sensing Network (MESN), buoys that collect near-realtime environmental data in Singapore’s coastal waters. It was my first big collaborative project where I got to interact with engineers, coders, developers, oceanographers, chemists, and end-users from academia, industries, and agencies. Although I had used environmental sensors before as a marine biologist, trying to set up a system to collect, ensure quality control, and disseminate marine environmental data on this scale was a really new and eye-opening experience. I am still involved part of the time as a field team member responsible for sensor maintenance and data quality control. Visit Ombak to learn more about the data we collect via MESN.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Singapore’s reefs are already quite impacted by human activities such as coastal development and the work at our ports. Understanding how corals can tolerate temperature increases and finding ways to improve that is important because temperature spikes related to climate change will cause further impacts on our reefs. What we find out will contribute towards management decisions on how best to help our coral reefs survive and keep going despite climate change. You might have heard of the 100,000 corals initiative, the national effort that aims to outplant 100,000 corals in degraded reef areas to improve marine biodiversity. The information from our project will help answer questions such as “What kind of corals should we plant to create resilient reefs for the future?”

On the MESN side, Southeast Asia really lacks historical long term in-situ marine data at fine time scales, which is needed to ground-truth models and satellite-derived data. We depend on environmental models to make predictions about ocean-atmospheric circulation, and ensuring the accuracy and validity of those models is ultimately really important for future planning, especially under intensifying climate change. As a scientist working on the ocean, having a centralized, well-curated data source for environmental parameters available to us would also greatly help us interpret and understand ecological observations in the field. The project still has 2 more years to go, and I am hoping that we will be able to develop a robust system to provide reliable data for many years to come.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I previously worked in TMSI from 2013-2014. Then I last joined again in October 2021. I like how multidisciplinary TMSI is. As a field biologist I really enjoy working with engineers and modellers as I think an integrated approach is needed to solve many of the modern challenges in ocean science. The project-based nature of the work also keeps things interesting. Finally, I really enjoy working at the marine facility on St. John Island. It is like a magical escape from the populated city.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

I would stay in a coral reef. Ideally on some really isolated atoll somewhere in the middle of the ocean.

What are your hobbies outside of research?

I scuba dive and read for fun outside of research. I enjoy nature, hiking, food, cooking (chemistry experiments with delicious results), and just over a year ago I have taken up rock climbing.

Who are you?

I am Aloysius, a research assistant with TMSI! Apart from work I also play music (my main instruments being bass guitar and a little acoustic guitar) and am also deeply involved in church activities.

What are you researching?

Currently, I am part of the research team that works together with the Office of Naval Research (ONR) of the US Navy to better understand biofouling in our region. Biofouling is the term used to describe the unwanted growth of marine animals (such as barnacles, tubeworms and mussels) on man-made structures. These structures are everything from small pleasure crafts to large unmoving oil rigs. This growth can accelerate corrosion and structural failure. On moving vessels, biofouling increases fuel costs by increasing drag, and can also become a vector for the spread of invasive species.

Hence our research seeks to understand the processes by which biofouling occurs, field-testing of novel antifouling materials and coatings, and how various environmental factors affect the processes of biofouling and its correspondent community (e.g. the effects of climate change on biofouling).

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Singapore has one of the highest shipping volumes in the world. Combine that with the significantly higher rate of biofouling in the tropics versus temperate regions and Singapore becomes one of the global hotspots for biofouling. Most biofouling research is done in temperate countries and there are many research questions yet to be answered for the tropical regions. One such question we are actively pursuing is: “What are the impacts of climate change on biofouling in the tropics?”. One observable impact for instance has been a shift in the fouling community with barnacles decreasing in abundance in recent years. This shift would then affect how we understand and subsequently, deal with biofouling.

Additionally, Singapore (and Southeast Asia too) has numerous sensitive habitats near our shipping lanes and ports. These include mangrove and reef habitats which are known to be sensitive to changes in water quality. As many traditional antifouling coating and materials contain various levels of heavy metals (which are toxic in high concentrations) to deter marine growth, there is a need to balance between toxicity (which would lead to more efficacious antifouling materials) and its potential collateral damage on the environment.

One past example that documents the need for such a balancing act is that of tributyltin (TBT). TBT was extremely efficacious in its antifouling properties due to its high toxicity, but research showed that it caused much collateral damage when the coating flaked and leached TBT into the oceans. The damage included inhibiting reproductive processes for a range of marine organisms, and the suppression of marine mammal immune systems. This eventually led to its worldwide ban in 2008. Hence with expanding knowledge on our marine habitats, this complements our work in ensuring antifouling technology’s environmental impact is mitigated.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I joined TMSI recently, in the later half of 2023. When I was still an undergraduate, I had several run-ins with various TMSI staff and the general work of the institution intrigued me. I was already involved with marine research in university, having worked with fish and subtidal invertebrates. Hence joining TMSI felt like a logical extension to broaden my understanding of marine research in Singapore, and hence a good place to chart and decide where I would like to go in the future should I continue down the research path.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

Coral reefs have always filled me with wonder, and I remember being shocked when I first learnt Singapore had its own reefs. While we have lost a large amount over the past decades, the remaining reefs still have a significant amount of coverage on our shores and I can only imagine how they looked in their prime. Hence, I would love to stay near a pristine reef habitat!

What are your hobbies outside of research?

Apart from family time, music and church related things occupy most of my time outside research. Being able to make and play music with friends is just so exciting! Some of my favourite genres are rock and metal, with Avenged Sevenfold and Dream Theater at the top of my playlist.

Who are you?

I grew up and have lived most of my life in Norway, so in contrast to Singapore’s constant hot and humid climate my natural habitat spans from cold, dark winters to warm, bright summers (and everything in between). I have a Master’s degree in Cybernetics and Robotics from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and after graduation I worked 4 years with data science and data engineering in a consulting firm in Oslo before moving to Singapore.

What are you researching?

As part of the Acoustic Research Laboratory at TMSI, I focus on machine learning and signal processing. One major research area is bioacoustics. We have years’ worth of acoustic data collected from various locations in Singapore, both underwater around the Southern Islands and terrestrial recordings from the Singapore Botanic Gardens. We use these recordings to train models to automatically detect marine mammals (such as dolphins) and local bird species, allowing us to monitor these species over time.

Specifically, we train artificial neural networks to detect and classify a wide range of wildlife vocalizations from acoustic recordings. In machine learning, artificial neural networks are essentially nothing more than a combination of simple mathematical functions. When trained on data they can approximate more complex functions such as mapping an acoustic recording to bird species. By providing examples of what to pay attention to, a neural network can learn to detect the few dolphin whistles present in a hundred-hour long recording. Similarly, when dealing with birds, it can identify tens of different bird species within just a few minutes of recordings during their most active periods.

Before feeding the neural network acoustic data, we normally apply signal processing techniques to aid the learning process, for example by reducing noise or transforming the acoustic recordings into representations that are easier for computers to work with.

Aside from bioacoustics, I work on machine learning models to improve the data quality in the Marine Environment Sensing Network (MESN) – a project collecting real-time data on more than 30 environmental parameters in Singapore waters to equip researchers with data to better assess the health of the ocean.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

As the world’s population continues to grow, I believe it becomes increasingly important to find sustainable ways for humans and nature to coexist. Singapore has a surprisingly rich biodiversity for being a population-dense city-state and one of the first steps to preserve biodiversity is to monitor their ecosystems over time. Bioacoustics and ocean sensing networks (like MESN), coupled with machine learning, enable effective, non-invasive ways of doing this. As an example, knowing the seasonal movement patterns of dolphins allows Singapore to plan certain undertakings accordingly, such as shipping routes or land reclamation projects, to reduce the negative impact on dolphins from human activities.

Models, data, and insights derived in Singapore may not only benefit the region locally but can also aid conservation efforts in other parts of the world. This is especially true in the machine learning domain. Models tend to be data hungry but high-quality data is generally expensive to collect. Researchers with limited local data can benefit from models trained in other regions by using these pre-trained models as a starting point for their local models.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I joined TMSI two and a half years ago. Initially, I was intrigued by all the great work in the intersection between acoustics, machine learning and marine life. What stands out to me the most after joining, however, are my colleagues. I have never met a group of people more open-minded, curious, ambitious, and yet humble - a rare mix of qualities that are hard to find.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

Perhaps this is a sign of home sickness, but I think it must be in the Arctic Ocean (if properly dressed), among whales and orcas, occasionally relaxing on sheets of floating ice.

What are your hobbies outside of research?

I enjoy nature and staying active. I have a passion for skiing, but the only good thing about skiing in Singapore is that avalanches are rare. Nevertheless, after relocating from Norway I have got addicted to tennis and skiing is replaced with wake surfing every now and then. Apart from that, I enjoy travelling to learn more about the world and I am always up for some good food and wine.

Who are you?

I am a research fellow who is interested in coral reef ecology and environmental management. I graduated with a PhD from NUS, where I quantified key biological attributes, such as growth rates or susceptibility to stress of different species of corals so that we can effectively prioritise sets of species to suit different coral reef restoration goals.

For example, coral species that are more resistant to – or which can recover quickly from – bleaching, may be more suitable for deployment in areas that experience wide temperature fluctuations. Species that grow fast can also be prioritised over slower-growing ones to quickly form reef frameworks in denuded areas.

What are you researching?

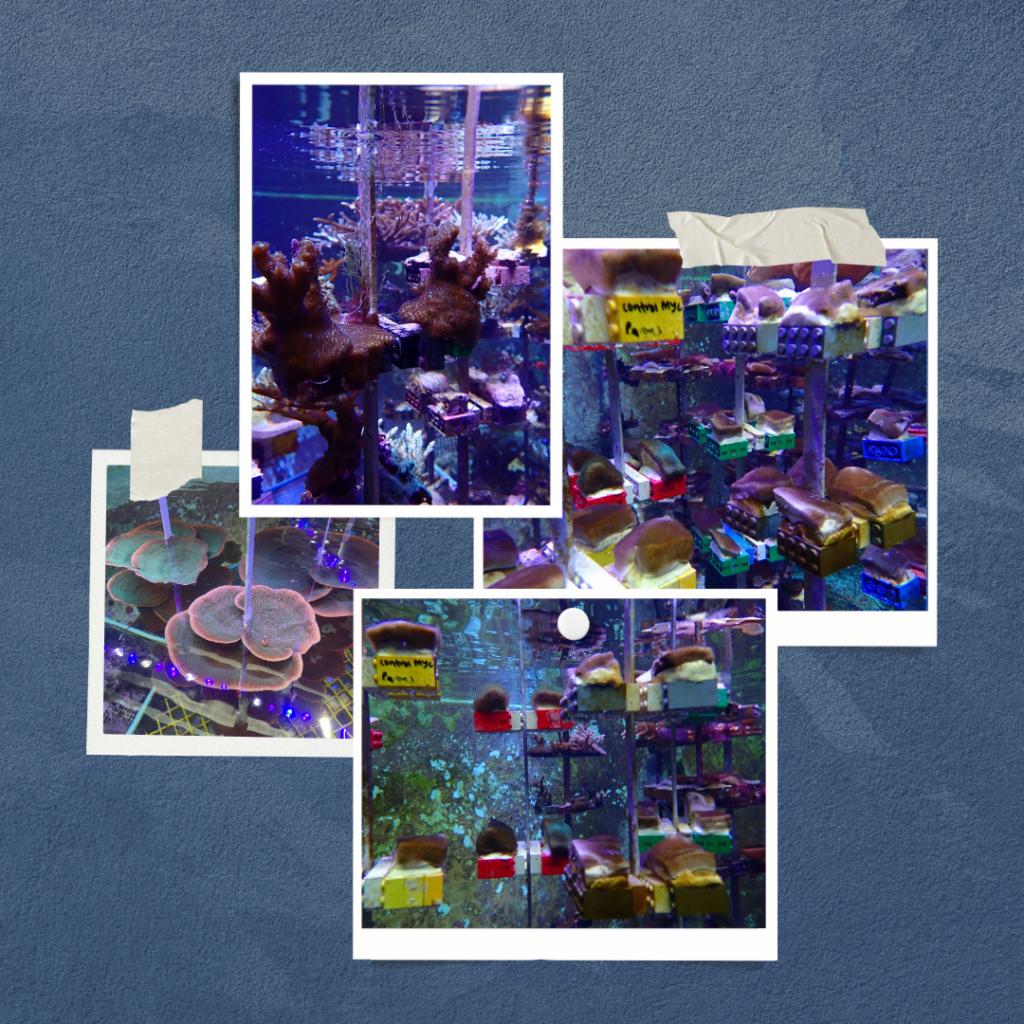

Currently, I explore and develop strategies to hasten the recovery of degraded coral reefs and urbanised marine environments such as Singapore’s. These strategies include innovating improvements to coral rearing practices - such as vertically farming coral fragments with the help of toy bricks - and identifying resilient corals to better withstand climate change conditions.

Growing corals on toy bricks suspended throughout the water column greatly increases yield in land-based nurseries, providing a steady pipeline of coral material to re-seed degraded areas and support other coral research.

I also test ways to boost coral establishment by monitoring how transplants of different coral species or sizes perform in different reef environments and carry out surveys to understand how Singapore's reefs fare over time.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Globally, large tracts of healthy reefs have been lost due to human and climate impacts, affecting the provision of critical ecosystem functions such as habitat and food. Active and targeted interventions such as habitat restoration and ecological engineering are needed to ensure that these functions can be sustained to continue supporting marine organisms and humankind. The strategies developed here are highly relevant and applicable to coastal and marine areas elsewhere that have been impacted by turbid and sedimented conditions, as well as urban pressures.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I first joined TMSI in 2008 as a research assistant, participating in various projects under different capacities, and then re-joined TMSI in 2021 as a research fellow. I like that the TMSI community, especially the Coral Reef folks, are an extremely innovative and passionate bunch who go over and beyond what they are tasked to do.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

Coral reefs, of course. They support a quarter of the world’s marine species so there is always something to see and do.

What are your hobbies outside of research?

Food and travel.

Who are you?

I am a chemical oceanographer by training, a mother of two and a balloon artist.

What are you researching? Tell us more about your latest achievement.

I am a research fellow at the Tropical Marine Science Institute at the National University of Singapore. I am particularly interested in how the marine environment has evolved over time and the interactions between human activities and natural ecosystems.

With the ongoing global warming caused by human activity, it is increasingly important to recognise how this warming can reshape the marine environment, thereby influence various aspects of our lives such as climate extremes, marine resources, and food security. To learn more about how the marine environment is changing in response to these climatic changes, I study natural archives like corals, and analyse their chemical compositions and isotopic signatures. The changes in these compositions and signatures reflect past changes in the environment, allowing me to reconstruct the historical environments in which these corals thrived. Through these reconstructions, I am able to journey centuries back in time to gain insights into the dynamic transformations within the marine environment.

For example, by reconstructing the lead concentration in corals from Singapore, Vietnam, Phuket, Chagos and Dongsha, I can visualise the changes in use of marine lead pollution over the past century. I found that the changes in lead concentration in coral corelates with the rise and fall of leaded gasoline. This is because like trees, corals form annual layers that provide a record on lead concentration in seawater at that time. This shows the importance of using clean fuel for us to achieve a low-pollution future. Fortunately, Southeast Asia phased out the use of leaded gasoline by around the year 2000, and this has caused a decrease in lead concentration in the seawater regionally.

My research in the marine pollution caused by leaded gasoline piqued my interest in clean fuel research. I am also involved in an ammonia bunkering project with collaborators from the Maritime Energy and Sustainable Development Centre of Excellence, the Nanyang Technological University and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research. The project aims to look into the potential of ammonia as a clean fuel source for the maritime industry, and to develop mitigation measures and environmental impact of using ammonia. Ammonia is considered a low-carbon fuel source that is cleaner than the traditional bunker fuel used by ships. It is also readily available, as it can be easily synthesised from air and water. But ammonia can also act as a fertiliser in the ocean, which can cause algal blooms. Because of this, it is important to be prepared for the potential environmental impact of the use of ammonia as a fuel for the shipping industry. This is my role in the project, which was recently selected as a spotlight project by the Singapore Maritime Institute, and people can learn more about the project here: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7115606872216268800

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Understanding oceanographic processes for Southeast Asia and Singapore is crucial for various reasons. Southeast Asia is a maritime continent where millions of people live within 100 km from the coast and heavily rely on the sea and marine resources for their daily subsistence. Understanding ocean processes helps in the management and sustainable use of marine resources, ensuring the livelihood of millions of people.

Southeast Asian countries have also been intensively industrialising over the past decades. Understanding ocean processes will help us delicately balance economic development, environmental sustainability, and food security.

Singapore, as a developed Southeast Asian country, is not only connected with the region through its seascape but also serves as an example and reference point for human-ocean interactions. What we learn from marine environments in Singapore could provide reference points for other areas in the region.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I joined TMSI in 2019.

TMSI is a research centre of excellence in tropical marine science and engineering, as well as environmental science. With its multi-disciplinary research laboratories and active international links, TMSI plays a strong role in promoting integrated marine science R&D.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

I am an oceanographer, but I am much more comfortable living on land!

What are your hobbies outside of research?

Balloon sculpting. I picked up balloon sculpting to cheer up my daughter in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. The hobby developed and I am now a semi-professional balloon artist.

Who are you? What is your background?

Everyone calls me Sri (yes, I told them to!), in short. I grew up in Southern India, did my Masters in physics, moved to the United States for another physics Masters at Tufts before entering University College London (UCL), to get my PhD in Climate Science, in 2008. Currently, I am Deputy Director (Admin) at the NUS Tropical Marine Science Institute (TMSI), where I also head the Climate and Water Research Centre.

What are you researching?

Primarily, climate and its change using numerical models, as well their impacts on key sectors. Part of this involves making projections from global climate models relevant for Southeast Asia. This is known as dynamical downscaling.

Global climate models tend to be very coarse in resolution, meaning that the projections for how climatic patterns might change due to rising greenhouse gas emissions are for large geographical areas spanning hundreds of kilometres in length.

But for small countries like Singapore to better prepare for the impacts of climate change, whether rising temperatures or sea levels, we will need higher resolution data.

My work involves downscaling climate models so the outputs are more relevant for smaller regions. You can think of it as trying to make a very pixelated photograph (projections from global climate models) come into greater focus (developing finer-scale regional data from global models).

The work also involves research into weather at an even higher resolution – such as in cities – and I also look into weather-climate dynamics across Southeast Asia.

Currently, my team and I have taken up research related to extreme weather, urban climates, climate risks, food security and applications of artificial intelligence to weather/climate.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Southeast Asia is relatively under studied when it comes to climate science. Being one of the most vulnerable regions, climate change and its impacts are critical for a sustainable future. Singapore, being highly urbanised, also exhibits a strong micro-climate, where buildings and urban vegetation influences urban heat and even rainfall. It is both interesting and challenging to model such observed micro-climatic features at fine resolutions. I believe understanding local climatic changes within a regional context adds value to our climate change initiatives.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I came to Singapore in 2008 when I joined TMSI under the first-ever climate change project commissioned by the National Environment Agency. It has been a long journey here and rather, the only job I have had so far! 😊

We were one of the first teams in Singapore to undertake regional climate modelling (Dynamical Downscaling). The research diversity in TMSI is exemplary!

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

I am not much of an ocean guy in terms of my research but when I think about it, maybe Andaman islands, which I have yet to visit. Sigh! I am not a good swimmer!

My grandparents lived there for a couple of years and I have heard about the islands’ serenity and biodiversity. Never had a chance to visit!

What are your hobbies outside of research?

I am an Indian classical musician, both in the vocal and instrumental sense. I have been training on the veena - a traditional Indian instrument - for about three decades now. I had a vibrant circle of music friends when I was living in the UK, not so much here in Singapore. I am also crazy about having a big garden… hmmm.. not here, but back home! 😊

Who are you? What is your background?

I'm Lee Bee Yan, currently a Research Fellow with St John's Island National Marine Laboratory and Tropical Marine Science Institute, NUS.

I am a brachyuran crab taxonomist by training. Taxonomy refers to the science of classification, and brachyuran crabs, also known as true crabs, are a group of crabs that can be found in various habitats, from freshwater to terrestrial and marine environments. They are known as true crabs as they have characteristics that differentiate them from hermit crabs. For example, true crabs have 10 legs inclusive of their pincers/claws, whereas hermit crabs look like they only have six. This is because their fourth and fifth pairs of legs, while there, are greatly reduced.

Among true crabs, I had focused on one specific group of them – spider crabs – for my PhD, which I completed at NUS in 2018. These crabs are also typically known as decorator crabs due to their unique way of camouflaging – they stick other objects, including other animals and plants, on their bodies to ward off predators.

My research project for my PhD was to revise and redefine two species-rich groups of spider crabs, as well as looking at the spider crab diversity in Singapore. Using museum samples and recently collected samples, I found that many spider crabs from the genus Hyastenus and Rochinia were misclassified, with some specimens even belonging to a new genus altogether. I also described 12 new species of spider crabs.

The diversity of spider crabs in Singapore is not well-known. The last known checklist was published in 1963 with 26 species of spider crabs. Subsequently, various other species were listed as being present in Singapore waters. From my study conducted for my PhD, I found that we have up to 35 species of spider crabs known from Singapore.

Most recently, together with collaborators from Australia, I discovered a new species of deep sea spider crab found in Queensland. We found that it had spines that reminded us of a Marvel character, and so, we named it Samadinia hela, after the Asgardian goddess of death.

What are you researching?

Apart from crab taxonomy work, I'm currently also looking at the reproduction and larval development of brachyuran crabs. I'm interested to find out the larval development pattern of different species of brachyuran crabs found in Singapore and the region.

By studying the larval development patterns, we would be able to better understand their systematics, their biology, their dispersal potential and range, and responses to changes in various environmental parameters etc. We could also better understand how the crab larvae response to various cues that could facilitate their settlement and metamorphosis to its juvenile stage.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

The taxonomy of most brachyuran crab species is relatively well studied, however, there is a lack of information for the biology, behaviour, development, etc. of the organisms. By understanding the reproduction and development of the crabs, we would be able to develop culture protocols for the crab species in captivity. This could help with better understanding of the organisms’ conservation purposes as well as for more research to be conducted.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I officially joined TMSI in February 2020. The facility on St John's Island is the only offshore marine laboratory in Singapore with access to seawater for the culture of organisms as well as easy access to most intertidal and subtidal field sites.

What is your favourite coastal and marine habitat?

The mangroves! The changes in biodiversity between low tide and high tide, day and night. Always fascinating to observe the animals in the mangrove habitat.

What are your hobbies outside of research?

Scuba diving, travelling, watching dramas and movies.

Who are you?

I am a Research Assistant at TMSI and have a degree in Marine Biology.

What are you researching?

I'm currently looking at optimizing the culture protocols of cowrie snails – specifically the tiger and Arabian cowrie - and giant clams (Crocea clams). This will allow us to successfully and efficiently produce juveniles in laboratory conditions. The research involves studying the diet of the larvae, water quality of the cultures, rearing conditions of juvenile clams and so on.

Why is this area of research important for Singapore / Southeast Asia?

Cowries and giant clams are popular in the aquarium trade industry and their shells are also commonly found in souvenir shops in many Southeast Asian countries. Both groups are heavily harvested from the wild and there is little legal protection, especially for cowrie snails. By understanding the reproduction and life cycle of the animals, we can develop suitable culture protocols to reproduce cowries and giant clams in captivity, and eventually scale up production to supply to the aquarium trade, or for research and conservation purposes.

When did you join TMSI? What made this institution stand out for you?

I joined TMSI in 2013. The facility on St. John's Island is Singapore's only marine laboratory, and being located on an offshore island, felt pretty cool then. It is still kind of cool now, but more than that, I appreciate the lack of traffic and crowds (for most part) on the island.

Where in the ocean would you like to live most?

Probably somewhere in the deep ocean.

I am familiar with coral reefs and intertidal shores, but the deep sea is somewhere I've never been before (and unlikely to go!). To me, it seems kind of serene and mysterious down below at those depths, so living there would be pretty great, although rather unattainable I suppose.

What are your hobbies outside of research?

Travelling and exploring other countries. I don't specifically choose countries near the sea, but I do like to visit coastal areas and enjoy watching sunsets by the sea. My favourite country is Japan, for the food and scenery!

Photos credit: Very!